There and back again: Writing Heroic Fiction with the Vogler Memo

Authors know that sinking feeling that can come in the middle of a first draft or deep into self-editing:

Where do I go from here?

Or maybe you have a killer opening and great idea for an ending, but absolutely no idea how to connect the two.

Get back to writing your novel with help from the Vogler memo, an important developmental editing resource based on the archetypal hero’s journey.

What is the Vogler memo?

In the mid-1980s, Christopher Vogler was a story analyst for Disney and had been a student of the famed mythologist Joseph Campbell.

To spark discussion about storytelling, he distilled Campbell’s seminal work of comparative mythology, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, to a seven-page memo and shared it around the office. In Hero, Campbell theorizes that archetypal hero stories from around the world all share similar fundamental elements.

Vogler knew Campbell’s teachings were invaluable to modern storytelling in animation and cinema, so he disseminated his memo to coworkers, scriptwriters, and producers in a much shorter, punchier, and less academic package.

By the decade’s end, the Vogler memo was all the rage in Hollywood, to the point where it was briefly plagiarized. Vogler eventually received proper credit for its creation and would later expand the short memo into The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structures for Writers.

Before we get Started

The Vogler memo isn’t a formula for perfect fiction. In fact, Vogler himself says that obsequiously following the hero’s journey can lead to stilted storytelling. Some of the principles below will occupy whole chapters in your novel. Others will fill a page or less. And others won’t appear at all.

With that in mind, let’s break down the stages of the Vogler memo to better understand how each step in the hero’s journey can strengthen your story:

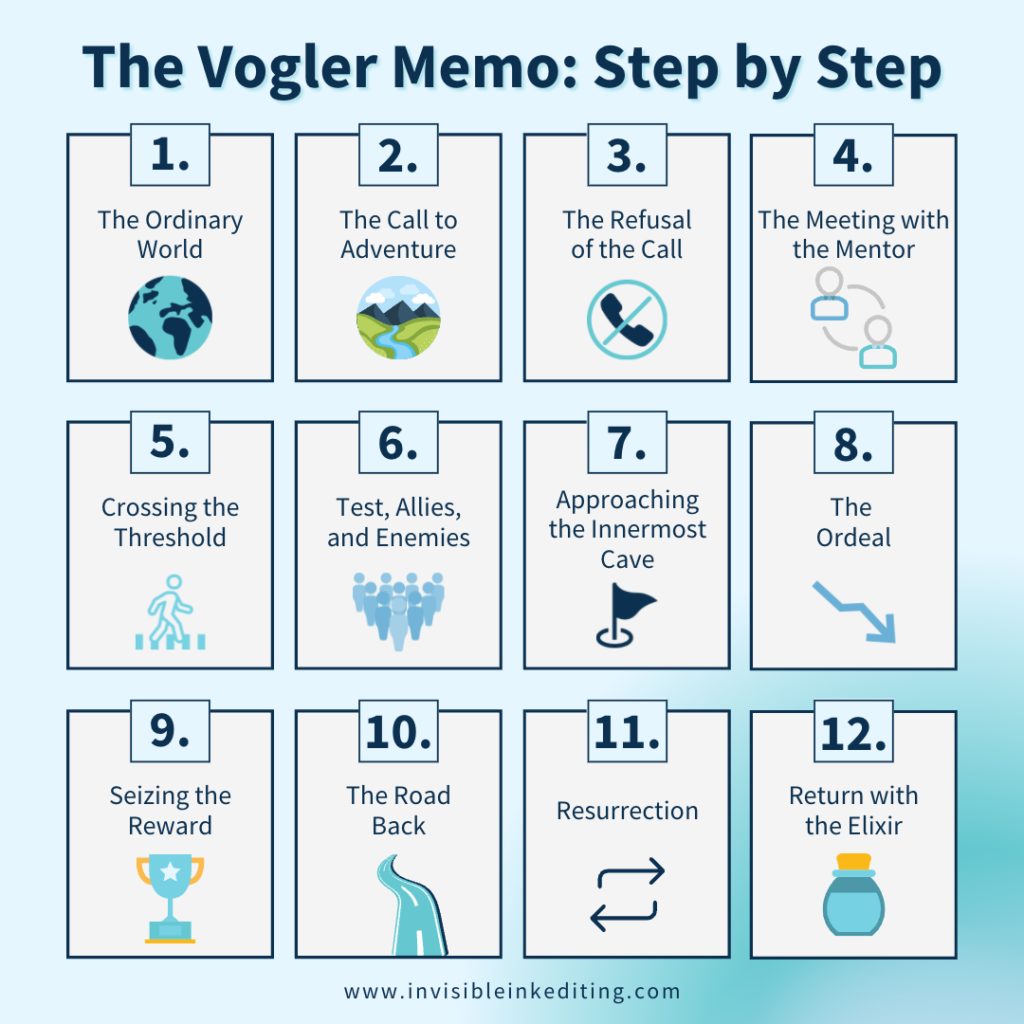

The Vogler Memo: step by step

1. The Ordinary World

There is an ebb and flow to hero myths: the protagonist goes off to complete their quest and returns home changed, or the protagonist’s home is taken and they must reclaim it. We seek the extraordinary or it comes knocking on our door when we least expect it.

In order to demonstrate this change, a story must establish an Ordinary World for the purpose of comparison. It’s as much a question of worldbuilding as it is about your main character. A strong Ordinary World will not only introduce the protagonist and the setting; it introduces the character in a context that a reader can relate to on some basic human level.

Sure, you may not know what it’s like to be a work-a-day urchin farmer from the seventh moon of Tib Talah, or a teenager from 1970s Minnesota too distracted by books on cryptozoology to land a babysitting job. But if that urchin farmer’s urchins were withering no matter how hard they toiled to keep them alive, we can all relate to that futility. And the babysitter? Sounds to me like someone who struggles to square their interests with their responsibilities.

I’ve been there. We’ve all been there. How will you demonstrate your protagonist’s humanity in your opening?

2. The Call to Adventure

Also known as the Inciting Incident, the Call to Adventure is an event in your story that prompts your protagonist into action and eventually sets them off on their journey to achieve a goal. For a detective to solve a murder mystery, for example, someone has to die under mysterious circumstances.

What propels your protagonist into the story is not always solely external. A police detective must solve the murder before them; that’s their job. But what motivates them internally, good or bad?

- Is this murder one of many, driving the community the detective swore to protect into fear, distrust, and chaos?

- Does the murder parallel the death of someone close to the detective whom he couldn’t save from their fate?

- Does the detective have a bad reputation or a traumatic incident they’re grappling with?

The Call to Adventure dovetails into the Refusal of the Call, the next stage of the hero’s journey, so let’s carry over the examples above for greater understanding of their value to your opening.

3. The Refusal of the Call

With your character’s humanity established and their call to adventure sounding loud and clear, it’s time for them to embark on their journey. Of course the detective will take the case eventually—or the knight will set out to slay the dragon, or the widower will start dating again, or whatever your genre demands—but the Refusal of the Call underscores the internal and external conflicts in the Call to Adventure, and establishes the consequences of not succeeding. These are the stakes.

Why and how might your protagonist temporarily reject the Call to Adventure or have the choice taken away from them?

- A family member of the victim confronts a detective about connections between the murders, which the detective doesn’t agree with—at first.

- Haunted by the death of a loved one, the detective asks the police chief to be taken off the case. But the chief knows they’re the person for the job.

- A small-town sheriff, now in their sixties, is on the brink of retirement, so the case is going to fall on the shoulders of a promising young officer. But the sheriff demands to be part of the investigation, so they’ll have to work with the promising young officer, even though they have wildly different policing styles.

Challenges like these give your character a central conflict or threat, and makes for a compelling, high-stakes plot.

4. The Meeting with the Mentor

Before a hero sets off on their journey, or before they even know they’re going to set off, they may consult with a mentor. The Meeting with the Mentor pushes the protagonist on their quest or provides them with special insight about the road ahead.

Be careful about the role your mentor plays in the greater story. Typically, the assistance a mentor provides comes from experience; they’ve been on a similar journey before. You don’t want their story to overshadow your protaganist’s unless it’s an intentional storytelling decision.

Avoid, however, a mentor who does your protagonist’s job for them. As Vogler writes in the memo, “Eventually the hero must face the unknown by himself.” In many cases, a mentor who sticks around beyond the first act of a story is later killed off or revealed to be a villain, giving them a new veneer and recontextualizing their guidance.

5. Crossing the Threshold

Crossing the Threshold is the first, intractable step your protagonist takes into the wilderness.

It doesn’t have to be much—you don’t have to linger in the doorway between worlds. But Crossing the Threshold should demonstrate how, at first blush, the extraordinary world of the adventure is starkly different from the Ordinary World established in the opening: a Martian landscape vs. a suburban neighborhood or a misanthrope’s world suddenly filled with romantic opportunities.

And remember, like other stages in the hero’s journey, the thresholds crossed can be figurative. Many zombie apocalypse stories, for example, take place in hometowns. The setting hasn’t literally changed, but how the protagonist and others view and interact with the setting does. What was once the local high school is now a fortified base of operations.

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Tests, Allies, and Enemies are the meat and potatoes of the second act. Here, your protagonist will undergo the trials as promised to your reader in the first act.

You can think of it in terms of genre expectations:

- A protagonist in a romance novel pursues love or strives to maintain it.

- A protagonist in a horror novel risks their life to confront the deadly unknown.

- A protagonist in a mystery novel hunts for clues and narrows down suspects.

- A protagonist in a heist novel puts together a team for the big score.

All the while, authors must pepper these genre expectations with conflict unique to their plot. How a protagonist faces the obstacles in their path is a direct result of the characterization established in the Ordinary World. A protagonist with nothing to lose will solve problems, acquire allies, and face enemies differently than a protagonist who has everything to lose.

7. Approaching the Innermost Cave

The structure of Approaching the Innermost Cave is a lot like that of Tests, Allies, and Enemies, except with a tighter focus on the protagonist’s ultimate goal. They are tangibly closer to achieving their heart’s desire, but immense obstacles still loom ahead of them, whether they know it or not.

The Innermost Cave can serve as a moment’s respite from the tribulations thus far, an opportunity for reconnaissance, or a heightening of the stakes. Think of the moments when Katniss returns to District 12 in The Hunger Games, or when Paul Sheldon sneaks around once Annie Wilkes finally leaves the house in Misery.

Whatever the case may be, use the Innermost Cave to remind the reader about your protagonist’s motivation, about the flaw that will prevent them (at first) from achieving their goal, and about the interpersonal relationships and conflicting motivations within the main cast.

If your knight is on a quest to slay the dragon in order to prove himself a worthy servant of their kingdom, the Innermost Cave might be the literal cave of the dragon’s lair. Do they place their helmet on the ground and pray for strength to face their fears? Do they survey the area to gather information? Even if your Innermost Cave is mostly an extension of Tests, Allies, and Enemies, what matters most is reinforcing your protagonist’s intangibles and showing the readers how close they are to their goal.

8. The Ordeal

By now, your story is deep into the second act, and it’s time for your protagonist to taste death, be it literal death or a spiritual death, as in the failure to achieve the core goal. It is the Black Moment, the Belly of the Whale, the Great Sacrifice.

Whatever the genre, the hero is brought low during the Ordeal. In a love story where the protagonist garners the attention of their love interest under false pretenses, this is the moment where the protagonist’s ruse is revealed right in front of their crush. In an action thriller, this is where the antagonist captures the hero, locks them away, and promises them a slow, painful death while their sinister plan comes to fruition.

Of course, scenes like these are all a setup; the protagonist will overcome the odds and ultimately achieve their goal. Death in the sense of the Ordeal is a precursor for rebirth. Your protagonist will “die” the flawed or incomplete person they were, but they will be reborn, transformed, ready to take on the antagonist anew and succeed.

9. Seizing the Reward

The treasure is within our grasp. Our hero has beaten death and now reaps the rewards for their sacrifice. They retrieve the Holy Grail. They defeat the villain. They learn the identity of the murderer. They prove themselves worthy.

Now having achieved their reward, the hero has undergone a transformation—either they changed in order to achieve their goal or the achievement of their goal changed them. Seizing the Sword can lead to the acquisition of magical powers, a new way of seeing the world, an epiphany about themselves or others.

10. The Road Back

Now that their goal is in their grasp, the hero sets a new goal, in many cases to return home or to set off on a new journey. What else is there?

Regardless, the antagonist, having been defeated, will rally in a last-ditch effort to thwart the hero, reclaim their power, or flee unpunished. As Vogler notes in the memo, Hollywood loves putting big-budget chase scenes in the Road Back.

The Road Back sets up one final confrontation in the following stage, a proving ground for the hero’s transformation. In many ways the Road Back therefore mirrors the establishing power of the Ordinary World and Call to Adventure stages.

11. Resurrection

And just like the Road Back is a miniature version of the Ordinary World and the Call to Adventure, the Resurrection is a miniature version of the Ordeal and Seizing the Reward.

Once again, the hero will face death and failure, but with the powers acquired earlier, they defeat the antagonistic forces once and for all. This is the climax of your story.

The goal is to demonstrate the change your hero has undergone at a crucial moment. It’s not enough to have them walk away with the sword, so to speak; they have to show that they are worthy enough to wield it. It’s not enough that the hero overcame their flaws when the chips were down during the Ordeal. This second opportunity in the Resurrection implies a more permanent change in character.

12. Return with the Elixir

The hero finally sets foot on familiar ground, returning from the unknown to the known. As explained in the previous stage, the hero has to bring back a piece of the extraordinary, otherwise the story was for naught.

Vogler adds that many comedies with foolish heroes don’t undergo a Return with the Elixir as stated, and thus the goofball protagonist leaves the audience feeling like they’re doomed to repeat the adventure all over again, having learned nothing.

Writing fiction with the hero’s journey

The hero’s journey outlined in Christopher Vogler’s memo, his book, or in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces are just storytelling principles, not unimpeachable rules. I’m hard pressed to name a novel without an Ordinary World or a Call to Adventure, but I can think of several without a Refusal of the Call or a Meeting with the Mentor.

And the hero archetype underpinning the narrative principles here do not align with all stories. We discussed, for example, how a comedy might have an inverted Return with the Elixir. A tragic hero might die during the Resurrection stage, though they may live on in spirit through the peripheral characters.

The point is, this timeless paradigm, found in stories across the globe, can strengthen the story you want to tell or help you fill in all the blanks you can feel but can’t name.