“Show, don’t tell.”

Nearly every writer will hear these three words at some point. You may have heard this phrase in a creative writing class, or from your beta readers or book editors. It’s by far the most common piece of advice we give out to our clients at Invisible Ink Editing.

There’s no doubt that showing vs. telling is one of the most challenging parts of writing fiction. Too much telling is also one of the top reasons editors and publishers reject a manuscript. Fortunately, with practice and dedication, you can overcome it. This guide will help you understand the issue better and give you the tools you need to defeat the habit of showing vs. telling once and for all.

Coming soon: Showing vs. telling worksheets

Once you’ve finished this article, check back soon—we’re currently putting together a number of worksheets for authors who want to improve their showing ability and reduce their telling tendencies. These worksheets will cover:

- Showing Plot | Overcoming exposition and summary issues

- Descriptive Telling | Understanding the difference between description and showing

- Real Characters | Making your characters do the hard work of showing

- Believable Dialogue | Dialogue tactics to show more and tell less

Be sure to follow us on Facebook or Twitter to get updates about this article and all of our advice for authors.

The definition of “Showing vs. Telling”

Let’s start with the basics. To understand showing vs. telling, you first need to understand what each of these words means in the particular context we’ll be discussing in this post.

Telling uses exposition, summary, and blunt description to convey the plot of a story.

Showing uses actions, dialogue, interior monologues, body language, characterization, setting and other subtle writing tactics to pull readers into your story.

Showing vs. Telling means your writing paints a picture instead of simply summarizing a story’s main points.

These are the most basic definitions, but it can still be a hard concept to grasp without examples. In fact, defining these concepts is an example of “telling”: You’re getting just the facts, and not much else.

If these definitions aren’t working for you, here’s a different way to think about showing vs. telling.

The movie theater scenario

Imagine this scenario: You’ve got tickets to see the new Ghost Heist IV, which came out last week. Ghost Heist III was one of the best movies you’ve ever seen, and you can’t wait to see the action-packed car chases, the spooktacular jump-scares, and the steamy paranormal romance.

You get to the theater and patiently wait in your seat, munching popcorn amongst the other chattering movie-goers. Finally the lights dim, and you wait for the opening credits to start rolling. Instead, you see a man walk out from backstage, pulling a stool behind him.

The man takes a seat on the stool as a spotlight illuminates him. He begins to speak in a loud voice:

“The opening credits are big and bold red letters,” he announces. “In the background we see a car chase in progress. One vehicle is a yellow truck, the other is the classic Ghost Rider van. They are in a nameless city…”

The audience begins to boo. A few people throw popcorn up on the stage, and soon they begin to file out of the theater. Utterly disappointed, you join the line outside to get your money back.

When people go to see a movie, they want to be transported out of reality for a couple of hours. They want to hear the big explosions and see the visuals in 3D. In other words, they want an immersive experience—that’s why theaters dim the lights and spend money on bigger, better sounds systems and screens. They don’t want to just be told the plot of a movie. They want to experience it themselves.

People read novels for largely the same reason—they want something that will take them to another world. If you rely on too much telling in your novel, you will become the man with the stool in the example above. Your readers will feel ripped off, because over-telling makes it impossible for them to feel immersed in the story. They need minute details, subtle hints, and realistic characterizations to truly experience the story.

Hopefully this helps you get a basic understanding of the importance of showing vs. telling. (If not, don’t worry—we have another example coming up a little later in this article.) In the next section, we’ll dig deeper to explore why too much telling and not enough showing can be detrimental to book sales.

Why too much telling is bad for readers

Think about what makes reading a good book so pleasurable. A novel you connect with can capture your attention for hours at a time and stick with you for years. You can fall in love with characters, or want to kill them, or be horrified by them. A good read is thrilling and exhilarating—and if a book really captures you in this way, then you know the author has done a masterful job of showing.

A book that tells too much, on the other hand, will leave the reader feeling flat or frustrated. Excessive exposition takes away some of what we love most about reading.

Telling murders suspense.

Showing in a novel is like leaving a trail of breadcrumbs for the reader. You want them to be compelled to turn the page, to find out what happens next. To do this, you need to drip-feed them information. It is true joy for a reader when a piece of information they picked up on page twenty-two becomes significant on page one hundred ninety-four. These kinds of joyous discoveries are one of the greatest aspects of reading, and why we often re-read our favorite novels.

If a good book is like leaving breadcrumbs for your reader to follow deeper into your story, then over-telling is like throwing a loaf of bread at them. By giving them all of the vital information at once, you take away the enjoyable experience a reader has of trying to figure out exactly what is going on. A reader goes into a book wanting to be entertained and perhaps challenged a bit—if they wanted “just the facts, ma’am,” they could read the synopsis of your novel and get the same emotional experience in a fraction of the time.

Telling puts up a wall.

Reading a good book should feel like jumping into the deep end of a pool. Once a reader opens the cover, they want to feel completely captured by the story. Reading should be a deep and immersive experience—which means the author needs to use deep and immersive storytelling tactics. Plain “telling” is the opposite of this. Instead of providing a diving board for your readers, you put up a wall that prevents them from getting deep inside the story.

Telling is just plain boring.

There’s no getting around it—telling a story is one of the most effective ways to bore your readers to tears. Without mystery and depth to keep them engaged, your readers will very quickly guess what will happen next, or else they won’t care enough to stick around and find out. Instead, they’ll put down your book and find something that draws them in and keeps them guessing.

Now that you understand why showing vs. telling is a big problem for your readership, let’s switch to the author’s perspective. Why is showing vs. telling such a common issue?

Why so many writers struggle with showing vs. telling

If you’re an aspiring writer, you’ve probably heard this before: “I also have an idea for a novel!” It’s something people often say after they find out you’re currently working on or have already published a novel yourself.

All novels start out as ideas, but not all ideas turn into novels. In fact, the sheer number of people who claim to have “a novel in them” is evidence that coming up with ideas is the easy part. Coming up with good ideas is the next step, and significantly more difficult.

Once you’ve got the kernel of a story, the real challenge begins: turning that idea into a fluid, well-written novel. The most challenging part is the act of translation from concept to compelling manuscript.

Related: How to write a novel from scratch

What so often happens for writers, particularly those just starting out, is that they put their idea down on paper and stop there. They see the act of writing a novel as writing down the details of the plot from start to finish. Even the most exciting, inventive plot, however, will still be just an outline if it’s written without a storyteller’s finesse.

What are some of the main challenges about showing that make it so difficult for so many authors?

Showing requires subtlety. Perhaps the biggest challenge of showing is to be able to convey the facts and nuances of your novel through subtle actions, descriptions, and dialogue. The other challenges outlined below all contribute to the overarching issue of subtlety.

Showing requires unbridled creativity. If you want to be subtle, you’ll need to be creative. A creative premise for your novel is one thing, but the true creativity comes when it’s time to put the pieces of your outline together in a way that hooks a reader and pulls them along to the last word.

Showing requires human understanding. Much of the art of showing has a foundation in human psychology. As a writer, you need to understand your characters better than anyone else—how they act, react, gesture, and speak. A realistic character isn’t an easy thing to conjure up, but a believable cast will make all the difference when it comes to showing.

Showing requires a diverse vocabulary. We’re not saying you need to use multi-syllabic words in every sentence, but you do need to have a vocabulary broad enough that you can convey the subtleties needed for strong showing in your writing.

Showing requires the ability to self-edit. The book editing process is vital for a number of reasons, one of which is the chance to eliminate some of the telling you may have done without realizing it. Heads up: This may mean “killing your darlings”—eliminating some of the passages of your novel that you love most dearly.

Showing requires trust in the audience. Often, authors end up over-telling because they are afraid their audience won’t understand what they are trying to say. While clarity is certainly important in any novel, a good writer must walk the tightrope between over-explaining and giving away just enough.

Showing requires practice. A lot of practice. No one is born a perfect writer, and nearly every major author who has dispensed writing advice has said something along these lines: If you want to succeed, you have to spend a lot of time writing.

The Little Red Riding Hood showing vs. telling example

Let’s look at another example of showing vs. telling, this time using a familiar story: Little Red Riding Hood.

Given that the story is a fairy-tale, most of the versions we know well are very much about telling, and not showing. In other words, it’s a simple story that’s usually pretty scant on details. For example, if you were to explain this story to someone who had never heard it before, you might say it like this:

Little Red Riding Hood was a young girl who decided to pay her grandmother a visit. On her way to her grandmother’s house, while passing through the woods, she encountered a big, bad wolf who tried to eat her. She ran off, but he was faster and got to her grandmother’s house first, where he promptly ate the old woman and dressed in her clothing. When Red arrived with her basket of treats for grandma, she saw the wolf and was immediately suspicious.

“My, what big eyes you have,” she said.

“The better to see you with, my dear,” the wolf said.

Red proceeded to make a few more comments about the size of the wolf’s ears, nose, mouth, and finally…

“Grandma, what big teeth you have!” Red said, feeling scared.

“The better to eat you with, my dear!”

The wolf grabbed Red and ate her.

A little later, a woodsman showed up at grandma’s house. He came inside and saw the wolf in grandma’s clothing, but saw through her disguise right away. He went over to the wolf and used his axe to cut open his stomach and pull Red out, safe and sound.

In this version of Little Red Riding Hood, you are only giving the details absolutely necessary to tell the story from start to finish. Remember the old police-movie phrase, “Just the facts, ma’am”? That’s a phrase you want to keep in mind when you’re writing, because if you’re just giving the facts and nothing else, you’re not showing a story—you’re providing a summary.

To bring the reader into the story, it’s important to include lots of details to draw a clearer picture. We won’t retell the whole story, but let’s start with one of the most exciting moments, when Red is examining her “grandmother.”

Imagine, instead, if an author wrote the story like this:

Red stepped over the threshold of her grandmother’s small cabin. Something smelled off—had Grandma left the eggs out on the counter again? Red wrinkled her nose. No, it wasn’t eggs; the smell was wilder and more gamey than that. Red clutched the basket tighter in her hands, feeling the wicker press into her fingers.

She looked over to her grandmother’s bed, and her stomach flipped. Grandma looked worse than she remembered. The old woman was wearing her favorite floral cap and matching gown, but the cap was pulled down so low that Red could barely make out her face. From the sides of her cap protruded two long ears, covered with wiry black and gray hair. Her ears stood straight up, pressing in the sides of the cloth cap and twitching slightly as Red spoke.

“Grandma… your ears. Are you all right?”

In the second version, we get many more details—we know how the cabin smells, what the basket feels like, what Grandma is wearing, what the wolf’s ears look like, and even a bit of history about Grandma’s tendency to leave out groceries. All of these details were absent from the “just the facts, ma’am,” version of the story.

It’s not just about drawing a clearer picture for the reader, but also providing subtle hints to the reader about our characters’ feelings and thoughts. In the first version of the above example, we are told that Red is “feeling scared.” In the second version, we are shown that she is feeling scared, because we know that her stomach flips, and we see her clutch her basket tighter.

Examples of over-telling aren’t always so obvious. In fact, the issue is typically more subtle, which makes it harder to identify. Fortunately, there are some red flags you can look out for in your own writing, as well as in the feedback you receive.

How to spot showing vs. telling

Though many teachers, editors, and readers are familiar with the phrase “showing vs. telling,” not everyone will use that exact wording. The reason? Too much telling and not enough showing in your story manifests itself in many different ways. Over-telling can affect everything from the overall plot of your novel to the conversations your characters have.

Telling words to watch out for

When you know your own plot inside and out, it can be very difficult to spot the instances where you are leaning more on telling rather than showing. However, there are some words that frequently seem to pop up like weeds around telling passages.

If you know telling is an issue for your current manuscript, it might be worthwhile to use the “find” function to search for some of these words:

Clearly/Obviously

Example Sentence: Maisey flashed a wide grin at Ben, obviously finding his joke funny.

Why it’s telling: In this case, we have an example of “over-telling.” The writer has actually done an ok job showing us that Maisey found the joke funny—a wide grin is an expression that suggests she found his comment humoros. Everything that follows the comma is unnecessary. If something is truly obvious or clear, it probably doesn’t need to be spelled out for the audience. If you are using the word “clearly” or “obviously” to explain something that isn’t obvious or clear, then you should instead find a way to use a gesture, piece of dialogue, or something else to show the audience what you want to convey.

How to show it: Maisey flashed a wide grin at Ben.

Told/tell/tells

Example Sentence: I told Layla the truth about everything—even about her father’s true identity.

Why it’s telling: Not surprisingly, the verb “to tell” can be an indicator of too much telling. Sometimes, it’s necessary to summarize dialogue that isn’t vital to the plot or to recap information the reader already has. Other times, though, summarizing dialogue is a lazy way of “telling” something rather than showing a conversation. Let’s assume that in this instance, Layla hasn’t yet learned the identity of her father, and that this is a turning point for her character. It would be much more exciting and engaging for the reader to see the actual dialogue and watch the expressions on Layla’s face, rather than simply be told that the conversation happened.

How to show it: “Layla, I-I don’t know how to say this,” I said, looking her in the eyes, “but your father was the man behind the wheel that night.”

“What are you saying?” Layla’s voice was suddenly high-pitched. Her mouth opened and closed a few times, but no words came out. She took a deep breath through her nose and let it out in a shaky exhale. “You’re joking, right?”

Pretty Language

Example Sentence: Keith felt a wave of despair wash over him as he watched the key disappear into the water.

Why it’s telling: Sometimes telling likes to cloak itself in pretty language. This may not seem like an example of telling, because of the florid language—despair “washing over” the character—does paint a bit of a picture. However, the author is still coming out and telling us exactly how Keith felt, rather than giving us visual or internal clues. For example, Keith could let out a cry or whimper, or he could desperately reach forward to try to catch the key, or he could think to himself, Oh no! Any of these options would put more showing into this sentence.

How to show it: A pained whimper escaped Keith’s lips as the key disappeared below the murky water.

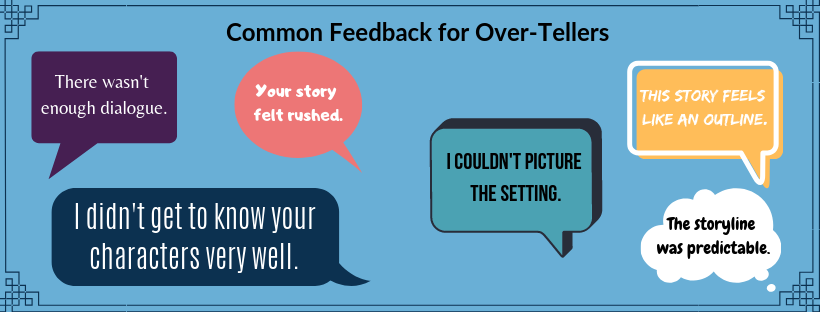

How to spot showing vs. telling in feedback

If you find it difficult to spot over-telling in your own work, it’s likely that your beta readers or editors can help you spot it. However, not everyone uses the term “showing vs. telling,” so criticism about this issue might show up under a different, harder-to-recognize moniker. Here are a few common types of comments you might see, and what they actually mean about showing vs. telling. (Don’t worry—our worksheets will show you how to address all of these issues.)

The feedback: Your story felt rushed.

What it means: Telling is very much like summarizing, and summarizing is what we do when we want to tell a story quickly. So it makes sense that too much telling will make a plot feel rushed.

The feedback: I feel like I didn’t know your characters very well.

What it means: The amount of “telling” in your story has alienated your readers from the characters. Telling is inherently a shallow way to tell a story, and it can make characters feel shallow as well.

The feedback: I couldn’t picture the setting.

What it means: Similar to above, the over-telling in the manuscript left out the vital descriptions and details that create a realistic setting.

The feedback: The storyline was predictable.

What it means: Too much telling can make readers feel like you’re hitting them over the head with the main plot points of your novel. Showing, on the other hand, uses subtle hints to lead readers through your story, keeping them hooked on wanting to figure out the plot on their own.

The feedback: There wasn’t enough dialogue.

What it means: If your novel has summarized conversations, rather than the actual dialogue, that means you are relying on “telling” the reader what your characters are talking about, rather than letting them speak for themselves.

The feedback: Your story feels like an outline.

What it means: This one is a no-brainer. “Telling” a story is basically like outlining it for the reader. If you see this, you know it’s definitely time to work on your “showing” skills.

If any of this feedback sounds familiar, or you think you might be too prone to telling and want to get better at showing, you’re in luck. Our team of editors is currently working on a number of showing vs. telling worksheets that will give you prompts and guides to improve your own showing skills. Check back soon, or follow us on Twitter or Facebook for updates!

5 replies on “How to master showing vs. telling Show more and tell less to build a compelling novel”

Thank you, the information was very helpful.

This is indeed a very good article. I enjoyed reading it. I believe striking a balance between telling and showing is very hard. Then learning showing part of story is also a myth.

Absolutely love this article. Fabulously done. It would be nice to read the complete “show” version of Little Red.

Some of the do-this “show” examples are painful to read. They’re so saccharine and overdone. E.g. A pained whimper escaped Keith’s lips as the key disappeared below the murky water.

Have you never read Hemingway or Jane Austen or Virginia Woolf? None of them write like that.

Nevertheless, I have certainly been told by editors & agents that there is too much tell in my work. Reading this helped me clarify a few things. Thank you.

Wow, I was confused and struggling with this concept. This essay really cleared it up for me, thank you so much!